Pedagogical model

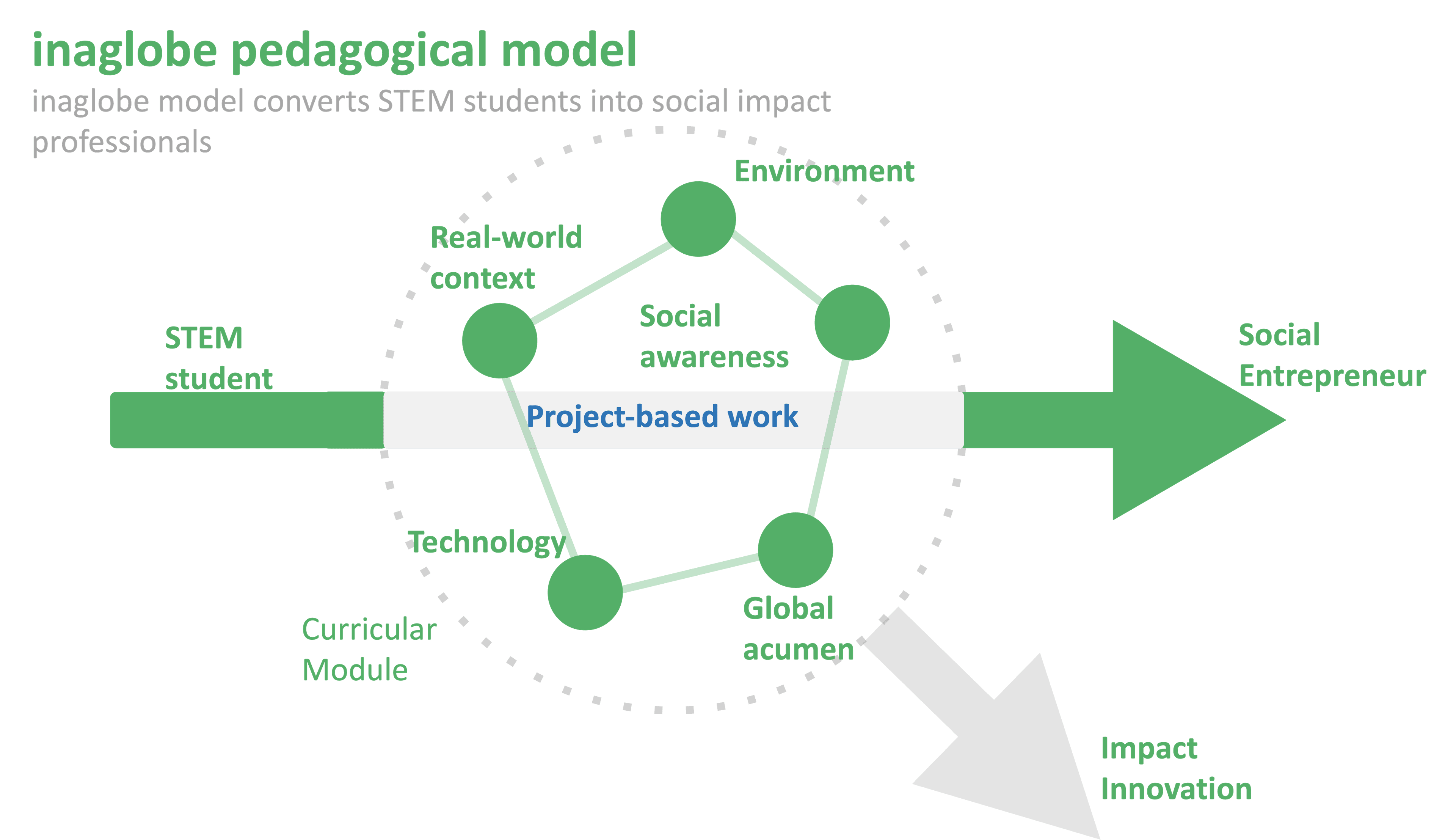

What we wanted students to learn – and how our pedagogical model turns STEM students into socially aware, globally capable practitioners.

Overview

The inaglobe pedagogical model has been the process under which we consider to have made the most impact. Beyond the impact that each individual project could have, it is the systemic change we were proposing to curricular project-based learning that we deem our core ambition. At the end of the day, projects may or may not have their intended impact, and are dependent on many factors that are often hard to know a priori. On the other hand, the student we are helping educate, the student we are exposing to a certain set of problems, in a certain context, with certain stakeholders, we intend to elevate the humanity of their technological innovation.

What we mean by humanity

What we mean by humanity here is:

- More human-centred

- More accessible, either by design, or by cost

- More real: inspired from a real need, rather than a hypothetical one – and with it the messiness of designing for the real world rather than for a lab

- More implementable: by definition, our problems come from an expressed need, therefore they are not hypothetical (unless they are blue skies projects)

We see the input into our system as a STEM student (although the reality is that our ambitions included students from all kinds of domains – the model was designed to be entirely replicable). And the output was what we call a "Social Entrepreneur", which for us is shorthand for a "socially aware and globally capable do-er" – someone with the sensitivity to understand the needs of the people, can design for people anywhere and can then build for them. This made our pedagogical model a student-centric model, where we regularly involve the feedback students provide us, and include them in co-creative sessions of what inaglobe should be.

Learnings from our experiments

We have tried several different things over the years. We looked at the information that projects benefitted from if sourced prior to the student project starting, or whether certain aspects of the research were part of the student experience. We looked at whether projects in the formal curriculum differed from extra-curricular projects (it is very common to see impact work as philanthropic and charitable rather than a formal pursuit professionally or academically). We tried different types of modules, we tried different sizes of teams and we saw the nuance between different departments and their existing pedagogical and academic structures.

There were things that were ubiquitous:

- Project-based / experiential learning is overwhelmingly positive:

- It fulfils students more than content-based learning; however, certain content should be taught prior to engaging in real-world project-based learning – especially around design ethics. inaglobe members support different initiatives to create content that empowers students to enter social impact innovation work more effectively.

- Students feel like they learn more, and feel more confident and capable of going out into the world to contribute.

- Project-based learning breeds entrepreneurship; social innovation project-based learning breeds social entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurs.

- Ownership: students working on real-world projects feel a stronger sense of ownership over outputs and outcomes than those working on hypothetical briefs.

- Sustainability of projects is multifactorial – environmental, social, economic, political, and cultural. Real-based projects with access to real people introduce students to all these factors, with the intent of designing for or around them.

- Access to stakeholders, beneficiaries, and contexts is critical. It gives a face and a name to the people students are designing for, and exposes them to the complexity of designing for someone whose needs may be very different from their own, and of planning testing and roll-out in those contexts.

- This is also deeply ethical: students experience co-creative and collaborative design as a way of empowering beneficiaries by giving them ownership, not just as a way of generating ideas.

- Curricular learning sustains engagement better than extra‑curricular. Extra-curricular projects often compete with other priorities, which can reduce engagement and learning, especially when some team members disengage.

- A shared purpose improves team-based learning. A common mission helps teams assign independent roles and responsibilities while still working together as a unit.

- Cross- and trans-disciplinary teams matter. Some departments foster this more than others, and it shows:

- Bioengineering projects with mixed engineering backgrounds (electrical, mechanical, software) have often thrived.

- More isolated departments, such as Computing, sometimes saw students struggle more due to high specialisation.

- We experimented less, curricularly, with involving business or social science students, instead compensating through contextual inputs (cultural cues, design ethics, anthropology, etc.).

- Lean principles are especially relevant for social innovation. These are rarely taught deeply in STEM; in inaglobe projects, resource constraints invited students to think about leapfrogging and frugal innovation.

- STEM students often develop key soft skills through projects. Planning, milestones, breaking work into smaller pieces, and prioritisation are all strengthened. Much of our mentoring was about helping students zoom in and out, organise their work, and build project management skills that are universally needed in professional life.

Internal thinking & profiling needs

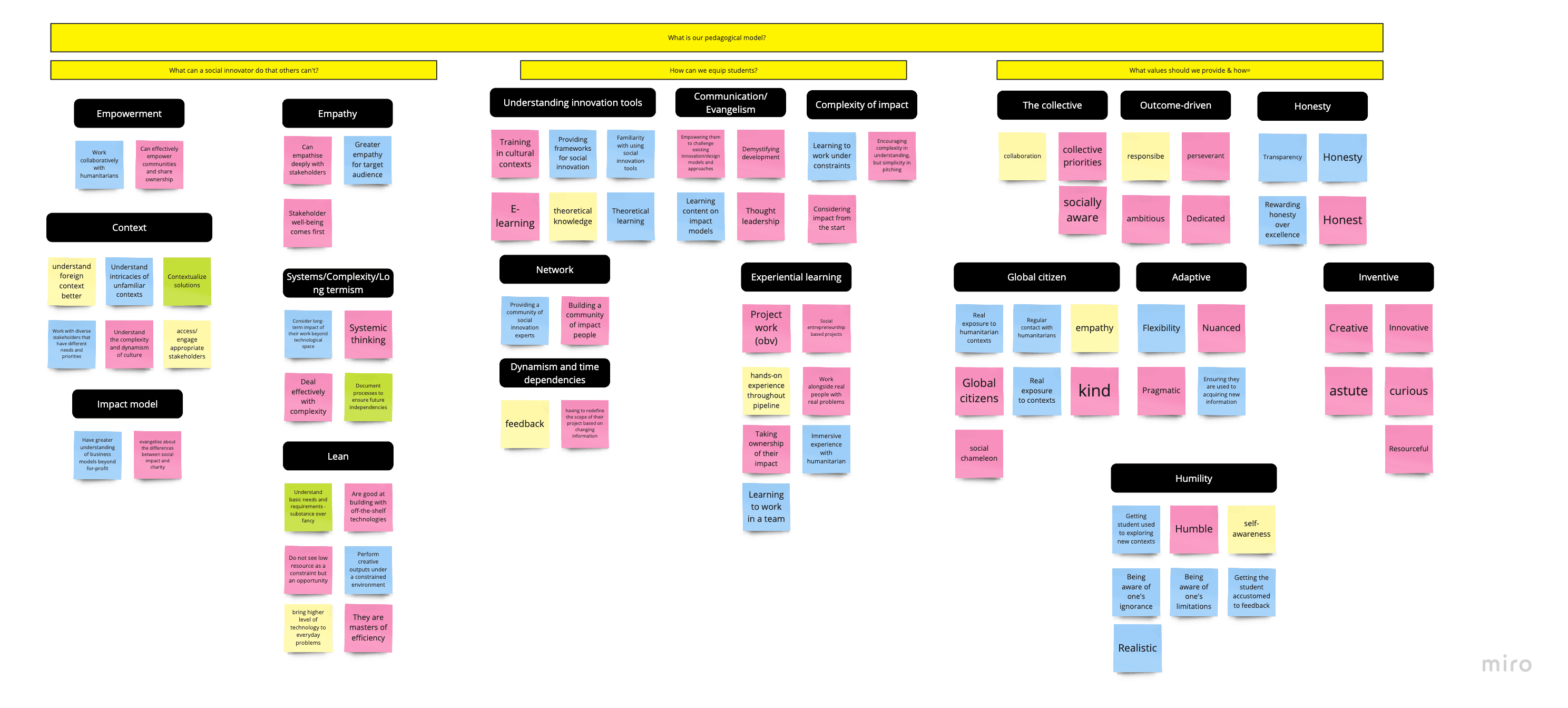

As a little insight into some of the internal thinking that was taking place at inaglobe, below you can see a brainstorming / collective intelligence session we ran to profile the needs behind our pedagogical model.